One of the worst maternal and child health emergencies in the world is unfolding in South Darfur, according to a report released by Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) today. In Driven to oblivion: The toll of conflict and neglect on the health of mothers and children in South Darfur, MSF explains how pregnant, birthing, and postpartum women as well as children are dying from preventable conditions as health needs far exceed what MSF can respond to.

For these crises to be addressed, the United Nations (UN) must act decisively to prevent further loss of life in Darfur. The UN must accelerate the return of its staff and agencies to Darfur and leverage all available resources and political influence to ensure that aid reaches those in need. Only a coordinated international response, supported by robust funding and unyielding pressure on the warring parties, can avert mass starvation and alleviate the suffering of millions.

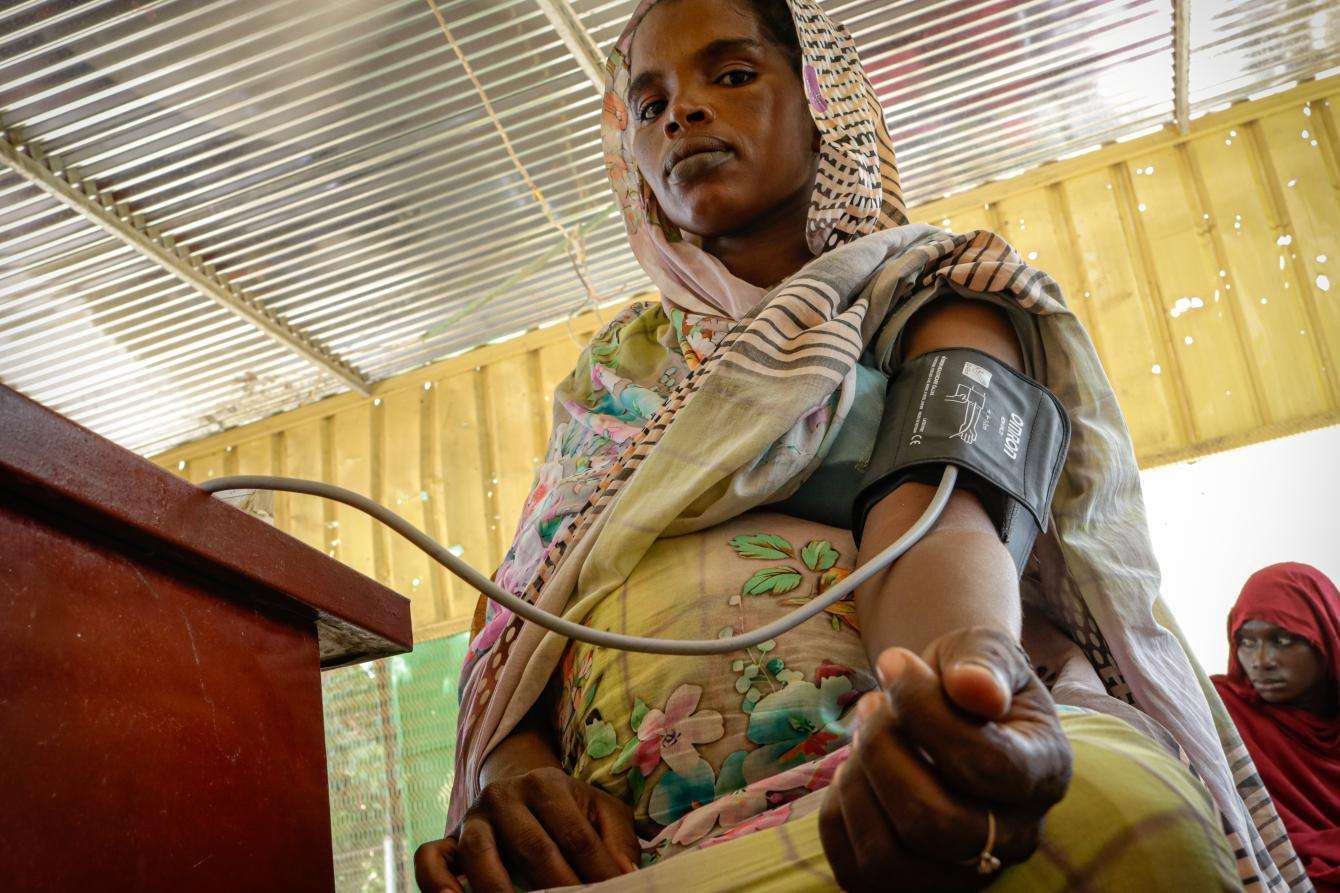

Fighting and insecurity in the Darfur region have forced pregnant women to flee and seek refuge in overcrowded and under-resourced camps, where access to quality maternal health care is nonexistent or severely limited. In a portion of South Darfur that MSF was able to assess, there were 114 maternal deaths from January to mid-August 2024, with a more than 50 percent increase in maternal deaths at medical facilities during this period.

Driven to oblivion

The toll of conflict and neglect on the health of mothers and children in South Darfur

A screening of children for malnutrition also found rates well beyond emergency thresholds. “This is a crisis unlike any other I have seen in my career—multiple health emergencies happening simultaneously with almost no international response from the UN and others,” said Dr. Gillian Burkhardt, MSF sexual and reproductive health activity manager, in Nyala, South Darfur. “Newborn babies, pregnant women, and new mothers dying in shocking numbers. So many deaths are due to preventable conditions, as almost everything has broken down.”

Critically ill women delay care due to distance and transportation costs

From January to August in South Darfur there were 46 maternal deaths at Nyala Teaching Hospital and Kas Rural Hospital. The scarcity of functioning health facilities and unaffordable transportation costs mean many women arrive at hospitals in critical condition, with 78 percent of maternal deaths in Kas and Nyala hospitals occurring in the first 24 hours following admission.

Lack of sanitary conditions can be a death sentence

Sepsis was the most common cause of maternal deaths in MSF supported facilities in South Darfur. The dearth of functioning health facilities forces women to give birth in unsanitary environments lacking basic items such as soap, clean delivery mats, or sterilized instruments. Such basic items could prevent infections that can be treated with antibiotics, but they are in short supply.

“A pregnant patient from a rural area waited two days to collect the money needed to get care. When she traveled to a health center, they had no drugs so she went back home,” explained Maria Fix, MSF medical team leader in South Darfur.

“After three days, her condition deteriorated, but again she had to wait five hours for transportation. She was already in a coma when she reached us. She died from a preventable infection.”

One in five newborns with sepsis did not survive

The crisis in South Darfur extends to children with thousands on the brink of death and starvation while others die of preventable conditions. From January to June 2024, 48 newborns died from sepsis in just two MSF-supported facilities, meaning one in five newborns with sepsis did not survive.

In August, 30,000 children under 2 years old were screened for malnutrition in South Darfur. Of these, 32.5 percent were found to be acutely malnourished, well beyond the WHO emergency threshold of 15 percent. Furthermore, 8.1 percent of children screened were severely acutely malnourished.

Nyala, the capital of South Darfur, used to be a hub for humanitarian organizations before the war but most organizations have not returned. The UN still has no international staff in the city, leaving MSF one of the only international organizations present. Between January and August, MSF teams in South Darfur provided 12,600 pre- and postnatal consultations and assisted 4,330 normal and complicated deliveries.

A disgraceful disparity between needs and response

Throughout Sudan, interrelated crises have compounded to cause immense suffering. Very little help is available, explains Dr. Burkhardt, who worked in North Darfur prior to her assignment in South Darfur.

“The disparity between the huge needs for health care, food, and basic services, and the consistently lacking international response is disgraceful. We call on donors, the UN, and international organizations to urgently increase funding and scale up and supply maternal health and nutrition programs.”

“We know that Sudan is a challenging place to work, but waiting for challenges to disappear by themselves is getting nowhere. For thousands of mothers and children, it's already too late. Risks must be managed and solutions found before yet more lives are lost.”

Conflict is also driving the maternal and child health crisis, subjecting people to violence and displacement. Supply shortages have been aggravated by the warring parties which, along with their affiliated armed groups, continue to block or restrict access to lifesaving aid.

The crisis risks trapping families in protracted cycles of malnutrition, sickness, and deteriorating health spanning generations.

A patient caretaker described the impact of the crises on their family: “The mother of the twins died from severe bleeding, leaving behind eight other children. My husband and I try to take care of them ... we don’t earn enough to feed them. Now we’re 13 in the house. We’re struggling, eating porridge and sauce with a bit of salt, little or no oil, and green leaves.”

What MSF is calling for

As we continue to respond to urgent medical needs in Sudan and the consequences of the ongoing conflict on women and children, MSF calls for:

- Unrestricted humanitarian access to Darfur. All available cross-border and cross line access routes must be opened so humanitarian supplies can pass through. The obstruction and diversion of aid must immediately stop. Critical infrastructure, including damaged roads and bridges, must be rehabilitated to support scale-up efforts. In the meantime, emergency alternatives such as boats must be considered.

- Increased attention and response to the maternal and reproductive health crisis. There is urgent need to scale up maternal and sexual and reproductive health program, as well as gender-sensitive nutrition and protection interventions. Barriers to access to care must be addressed, particularly for displaced communities.

- Immediate scale-up of emergency child nutrition services. Child malnutrition programs must be urgently expanded and adequately supplied with therapeutic food items. Food distributions and cash assistance to vulnerable mothers and families must be ramped up, particularly in conflict-affected communities.

- Immediate return of UN agencies to South Darfur. UN international teams must reestablish their presence in Nyala to coordinate the response from the ground and encourage humanitarian organizations to return. Senior UN leadership visits must reach South Darfur to raise international visibility of the crisis.

MSF’s work in South Darfur

- In Nyala Teaching Hospital the MSF-supported maternity unit facilitates normal and Cesarean deliveries and contraceptive services, and provides care to survivors of sexual and gender-based violence, including prevention of sexually transmitted infections, provision of HIV post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), and emergency contraceptives.

- At Al-Wahda Hospital MSF supports contraceptive services, and care for survivors of sexual violence through the provision of incentives and technical support.

- In the Bileil Primary Health Care Center in Nyala MSF supports pre- and postnatal care, normal births, and contraceptive consultations.

- In Kas Rural Hospital MSF supports secondary health care and comprehensive emergency obstetric and neonatal care.

- In the South Jebel Marra region, MSF is supporting three primary health care facilities (Kalokitting, Torun Tonga, and Dili) that provide pre- and postnatal consultations, contraceptive services, and emergency referrals to Kas and Golo hospitals.

- In addition to supporting these facilities, MSF is supporting women’s clinics at sites for internally displaced people including Kalma, Dreij, and Otash outside Nyala, and will start supporting similar women’s health services in in the coming weeks to address the surging maternal mortality and sexual and reproductive needs across the state.